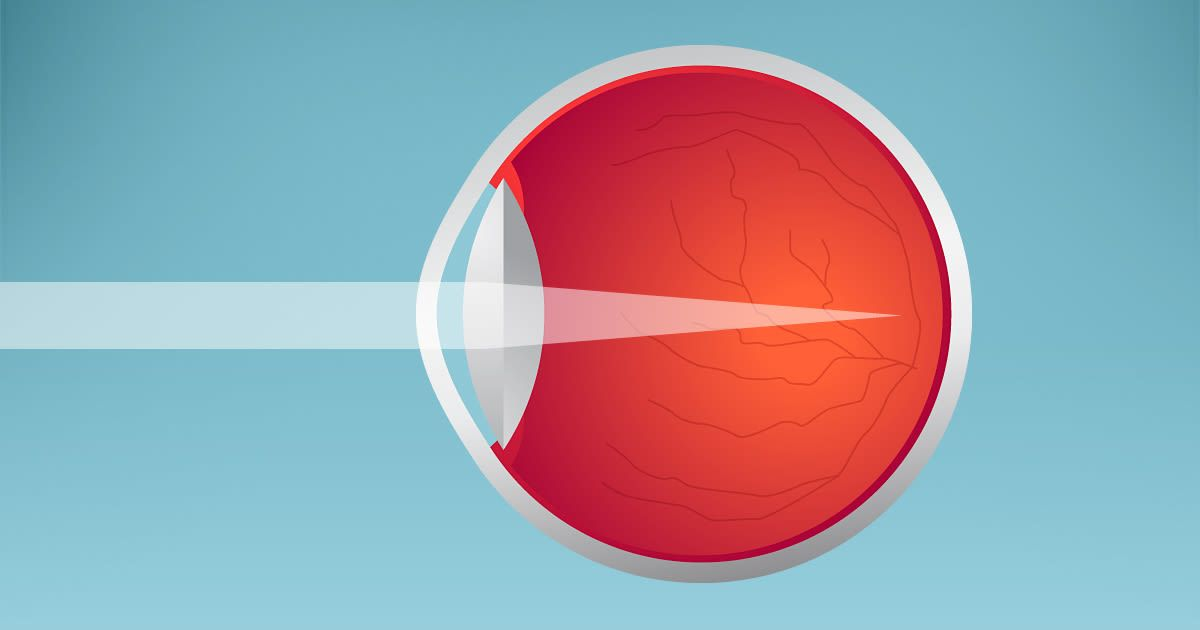

Recent decades have witnessed a significant increase in myopia cases around the world, particularly among children and adolescents. Although myopia has long been classified as a simple refractive error, this classification has begun to be seriously questioned in scientific circles, especially with mounting evidence of its association with serious visual complications and its increasing impact on public health.

Until recently, myopia was considered a visual condition that could be corrected with glasses or contact lenses. However, recent studies have shown that advanced forms of myopia—known as “high myopia”—are associated with structural changes in the eye that can lead to complications such as:

These complications prompt us to reconsider the classification of myopia, not just as a refractive condition, but as a chronic condition that requires early diagnosis and thoughtful preventive intervention.

A number of prominent scientific bodies, such as the US National Academies and the American Optometric Association (AOA), have begun to explicitly call for myopia to be considered a disease. These recommendations do not come out of nowhere, but rather are based on alarming epidemiological and clinical data indicating that the incidence of myopia could reach more than 50% of the world's population by 2050, according to World Health Organization estimates.

From this perspective, addressing myopia seriously becomes a professional and ethical imperative. It is not enough to perform visual correction; we must also strive to implement prevention and slowing methods, including:

As an optometrist, I believe that classifying myopia as a medical condition is an inevitable next step, especially in light of the evolving scientific evidence. This classification is not intended to raise alarm, but rather to promote prevention, improve the quality of vision care, and ensure a better visual future for our future generations.